“Meat every Sunday and ground meat on Thursdays”—this was the rule around which my mother, and most Greek women, planned meals when I was growing up. The rule wasn’t invented for the health-conscious, and certainly wasn’t for those who wished to lose weight—rather, up until the 1960s, hardworking Greek men could barely afford food for their families. Malnutrition, rather than obesity, was the country’s epidemic—and meat was very expensive, as it was never plentiful in Greece, a mountainous country with no plains for raising cattle. Instead, farmers raised mountain goats and sheep, but primarily for milk and cheese. I often wonder if the current Greek obsession with roasted baby lamb, pork and other meats is a result of the fact that, for many years, meat has been a rare luxury—a festive dish enjoyed only on important religious and family occasions.

We know now that today’s over-consumption of meat is unhealthy for our hearts, our waistlines, and our planet. The mass production of meat—meant to satisfy the increasing needs of an expanding population—is unsustainable, and a terrible waste of resources. To add to the problem, pesticides, hormones and methane gas (from livestock manure) have become a significant source of pollution.

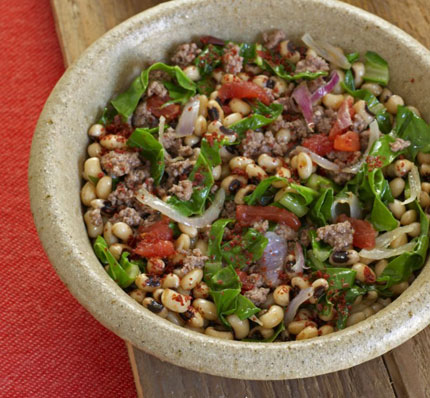

For both environmental and culinary reasons, we look back at the traditional Mediterranean dishes that ingeniously used meat as flavoring—rather than as a primary ingredient—to create healthy, one-pot family meals with vegetables, greens, and beans. The Black-Eyed Pea, Ground Lamb, and Chard Stew is a delicious example: it seems to be tailor-made by a modern nutritionist but is, in fact, adapted from Gaziatep—the part of southern Turkey that borders Syria. This, and many other recipes, may be found in my upcoming book, Mediterranean Hot and Spicy.

The Sunday meat dishes of my childhood were usually based on a piece of local, free-range veal. This was the most common meat in those days, and about 2 ½ pounds, with the bone, was enough to create a hearty meal for our family of four. Mother started cooking on Saturday afternoon: the meat was stringy and tough, and would simmer for an hour with a quartered onion, a good pinch of sugar, and 2-3 tablespoons of olive oil to soften. She left the meat to cool overnight in its juices, then, on Sunday morning, cooked the meat on high heat until most of the water evaporated. She then cut the meat into slices or cubes, discarded the bones, and returned the pieces to the stove to sauté in their fatty sauce.

At this point our Sunday meal could go in two directions—it could become either kokinisto (tomato sauce with potatoes, pasta, or rice; eggplants, zucchini, green beans, or any other seasonal vegetable) or—for most winter Sundays—lemonato. With white wine, several potatoes, and plenty of lemon juice, the meal simmered until the potatoes were tender. I never cared much about the meat—but I couldn’t stop eating the sweet, sour, lemony potatoes that had cooked in the meat’s delicious juices.

Thursdays meant keftedes—meatballs, which were served in most homes. Ground meat—usually veal, sometimes mixed with pork—was combined with an almost equal amount of soaked bread to make the ingredients go further. This was flavored with herbs and spices, shaped into walnut-sized balls or larger patties, coated with flour, and then fried in olive oil. Everyone loved keftedes, and resourceful cooks have invented all kinds of meatless varieties, including vegetable and bean patties. Zucchinis, squash, tomatoes, onions, fennel, chickpeas, lentils, nettles, wild greens —whatever was in season was chopped and mixed with breadcrumbs or flour and herbs. Spoonfuls were fried in olive oil and served warm or cold. Today, these meatless fritters, a main course in the old days, are usually served as mezze—often accompanied withskordalia (garlic sauce) or yogurt tzatziki.

I was never fond of the meat-heavy diet which is now the norm in Greece—instead, I look forward to the eggplant, zucchini or pasta that is cooked with, or accompanies, the meat—as does Costas. We often forget containers of leftover veal, pork, or chicken in the refrigerator—after eating the vegetables, the meat doesn’t appeal to us anymore. But our dogs, Melech and Popie, love the leftovers!