The few tourists visiting the Acropolis on a Monday morning, late February or early Mars are surprised to see a steady flow of people, young and old, walking up towards Philopappou Hill, across from the Parthenon.

Painting by SPYROS VASSILIOU

Braving the chill and occasional light rain, these locals seemed to head to a common destination for an outdoor lunch, carrying not just bags brimming with food but also multi-colored kites. They were Athenians who liked to keep tradition and celebrate Kathari Deftera (Clean Monday), the first day of Lent, out of doors. As is the custom, on this day people gather on this historic hill to eat, drink, fly kites and dance to the tunes of live bands provided by the city’s municipality.

If tourists have had the chance to look into the bags containing foods for this festive picnic, they would probably assume that Athenians had suddenly become vegetarians, or that they had decided to dedicate this early spring day to the renowned, yet hard-to-find, Mediterranean Diet. How else could anybody familiar with Greek customs explain a public celebration that does not involve roasted lamb, kid, or pork?

Early memories

I grew up in Patissia, now a densely populated Athenian working-class neighborhood. Up until the early 1970ies, Patissia felt like a village at the edge of the city. We shared a vast garden with my maternal grandparents, and two of my mother’s siblings and their families. I remember our Clean Monday celebrations back in those very hard, yet hopeful days right after WWII and the Greek civil war that followed it. All of our extended family and friends, more than forty people, gathered in our property. Aunts brought vinegar-marinated octopus, pots with cuttlefish risotto, vegetable pies and stews. We made large salads with the produce from our garden, and people never seized to praise my mother’s trademark rengosalata (smoked herring roe spread). Instead of taramosalata, the usual Lenten staple made with cured, pink-dyed cod or carp roe, my mother bought smoked herrings, choosing carefully fish with visibly swollen belly that contained eggs.

She used just these eggs –the herring roe–for her spread, beating it in a mortar together with spring onions, potato, plenty of freshly squeezed lemon juice and copious amount of fruity olive oil. She also painstakingly cleared the smelly herring fillets from the skin and bones–nothing was ever wasted in our home—to be consumed on another day, usually with our sweet bean or chickpea soups to balance the strong-flavored, salty fish. Nowadays whole herrings are hard to find, and I use the conveniently packaged herring fillets for the spread I prepare in the blender, following my mother’s recipe. Few people know, let alone observe the strict dietary rules.

To non-Greeks, our Clean Monday table probably sounds like a feast rather than a fast. The rules of orthodox fasting are somewhat peculiar, although they usually hide interesting explanations behind them. One of the basic commands is that no food containing red blood may be consumed. From this idea stem many unusual prohibitions. For example, although olives are allowed even on Holly Friday, olive oil is not, because in traditional olive pressing the olive pulp was passed between matts woven from goat’s wool. Similarly, only mollusks (octopus, cuttlefish, calamari), crustaceans (shrimp, lobster etc.) and fish roe are permitted; the flesh of fish that has even the smallest traces of red blood is considered ‘meat’, therefore not suitable for the Lenten table. In other words, fish roe, or even caviar are safely clean foods, most appropriate for that glorious first day of Lent; and so is wine!

The wine served at our family’s Koulouma was homemade, from barrels kept in our basement. My father, like most frugal Greeks, used to buy grape must from near-by vineyards, and proudly claimed that he added nothing to it, just left it to ‘boil’ and become ‘pure unadulterated wine,’ an expression I still hear from amateur wine producer with dread! That barrel wine was –and still is– just barely drinkable while still quite new–from November to Christmas. By February or March it had acquired a ghastly sour and heavily oxidized taste, complemented by the obnoxious rotten, old wood barrel odor, accentuated by the murky residue. That, of course, did not prevent our guests from drinking lots of it. An uncle played the piano, another was a professional violinist, and they accompanied the tipsy singing and dancing that lasted until late afternoon. We kids flied kites and played all sorts of games, trying to keep away from the embarrassing deeds of the grownups.

Definition and Description

The festive day of Clean Monday is also known as Koulouma. Some linguists claim that the word comes from the Latin ‘cumulus’–a mass or heap, a pile– but the logic behind their etymology is unclear. A more plausible theory is that the term derives from the word kolones (columns). At the turn of the 20th century, soon after Athens became the capital of newly born kingdom of Greece, Clean Monday festivities took place around the few upright columns of the ancient temple of Jupiter, not far from Syntagma square in downtown Athens.

With television and the media, this initially Athenian word has become known throughout the country, and today Koulouma is synonymous with Kathari Deftera –a public holiday in Greece. Difficult to say when the area around the temple of Jupiter, now fenced, was abandoned and the festivities moved to Philopappou; but one can speculate that the hill facing Acropolis is a far better spot for flying kites.

Kite flying adds an interesting twist to this unusual Greek celebration. Nobody knows exactly when kites became part of Kathari Deftera but it is almost certain that this flamboyant Asian custom, imported to Europe in the 19th century, was soon transplanted to Greece by cosmopolitan Athenians. In Bermuda, I read, kite-flying is part of the traditional Easter celebrations ‘symbolizing Christ’s ascent.’ I can’t tell you anything about the symbolism of kite-flying during the first day of Lent, but Kathari Deftera –or Koulouma— is not complete without them. If the wind is favorably light, the sky fills with multicolored kites. In the old days boys and their fathers would craft kites using local bamboo canes, cotton strings and multi-colored oil-papers glued with flour paste. Now, of course, people buy ready-made plastic kites, usually hideously displaying the insignia and colors of popular soccer teams.

Kathari Deftera is the equivalent of Ash Wednesday or Shrove Monday. It is tied to Greek Orthodox Easter and thus it is a moving feast based on the lunar calendar. Celebrated in late February or early March, it clearly resonates the Roman pagan Februa or Februatio festivals. These involved ritual purifications and were later incorporated with Lupercalia, the ancient, Pre-Roman pastoral festival, which included several practices meant to avert evil spirits, purify the city, and more importantly, bring health and fertility.

According to the official orthodox church, the Lent actually begins the preceding (Sunday) night at a special service called Forgiveness Vespers. Apokreo is the Greek word for Carnival and much like its Latin counterpart also means ‘to do away with meat’. It is the day women clean their pots and pans, getting rid of all remnants of meat, dairy and eggs that they cooked the previous Carnival weeks. Meat is banished after that till Easter Sunday. According to a mock wailing song from the Fthiotis region, in Central Greece:

“Clean Monday claims the death of Meat,

Cheese is moribund,

while Mr. Leek raises its tail

and Mr. Onion lifts its beard…”

The official character of Clean Monday is set by the first twenty verses of Isaiah read at the vespers:

‘Wash yourselves, make yourselves clean; remove the evil of your doings from before my eyes; cease to do evil; learn to do good; seek justice, rescue the oppressed, defend the orphan, plead for the widow. Come now, let us argue it out, says the Lord: though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be like snow; though they are red like crimson, they shall become like wool (Is 1:16–8 RSV)”.

I can’t help wondering if Isaiah’ prophesy comprise the crimson red kites of Olympiakos, the most popular Greek soccer team, whose followers include some of the most feared hooligans…

Daring Fertility Rituals

The popular celebrations of the first day of the forty-day Lent (forty-eight days, in fact) preceding Greek Easter could hardly fit into Isaiah’s dream of sober abstinence and repentance. No wonder the official church has shunned them for years, rightly considering them excesses of pagan origin that sneaked their way into clean Christian traditions. To the spite of the official church, the actual rituals performed during the first meatless day of each year feel more like a continuation of the preceding riotous Carnival festivals, that precede this day of supposed sobriety. The copious amount of alcohol consumed during the Clean Monday lunch loosens inhibitions creating wild celebrations, dances, and often daring folk performances with strong sexual connotations. Anthropologists trace the roots of these Dionysian feasts to ancient fertility rituals that marked the beginning of spring, supposedly to stimulate the earth and bring the plants to life after their winter ‘hibernation’.

In the north of Greece, one finds the most colorful folk performances traditionally practiced by the Sarakatsani and the Vlachs, nomadic groups of transhumant shepherds, as well as by the Thracian sinhabiting Greece and neighboring Bulgaria, as well as other Balkan countries, and the European part of Turkey. Angeliki Giannakidou, founder of the Ethnological Museum of Thrace, explained to me that the basic truths of everyday life through the ages are at the core of such rituals. Several practices of this kind stayed alive in the north, and in particular among the residents of the most fertile region of Thrace –was this not, after all the land where the god Dionysus was born? After Christianization, agrarian and pastoral populations continued to practice several ancient fertility and phallic rituals loosely incorporating them to the Christian calendar.

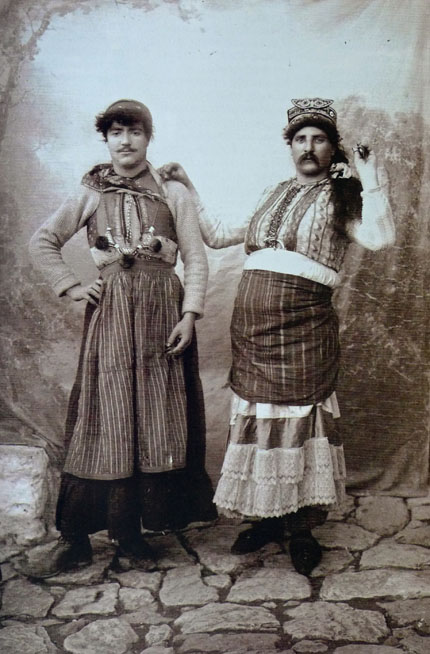

When groups of Vlachs and Sarakatsani later spread to southern Greece and the islands, they brought with them their colorful folk fertility performances. Most common is the mock Vlach wedding of Thiva, versions of which are also found in various parts of central Greece. This is a ‘wedding’ between two men, one of whom is dressed as the bride, wearing a bright red veil.

They are wedded by a mock priest or monk in a brief ceremony. Then, ‘bride’ and ‘groom’ dance before retiring to their wedding bedroom with their joyous entourage, where they pretend to copulate. Soon, though, the ‘bride’ kicks the ‘groom’ away, as not satisfactory enough, and samples various other males of the group, who are also eventually kicked out. Finally, the ‘groom’ returns for his final act –a mock act at that. Meantime members of the group dance and sing songs with suggestive lyrics, like “show us how the devil’s monks grind pepper,” laying on the ground and moving their bodies rhythmically as if copulating with the earth.

Another explicit fertility celebration is the borani of Tyrnavos. It is perhaps the most daring of all such folk performances. Starts with a maypole dance, something also practiced in Serres and other Macedonian cities. The main Tyrnavos event is the preparation of borani, a Lenten soup of nettles and wild greens. Gathered around the big boiling pot, men and women stir the broth reciting evocative poems and singing songs with explicit sexual references, while holding large clay phalluses.

On Skyros and other islands, scary-looking men take part in very noisy parades, covered with goats’ hides, with bells hanging around their necks and, suggestively, around their waists. Similar parades take place in the north of Greece, and on various occasions in Bulgaria and other Balkan countries, as well in Sardinia and other islands of the Mediterranean. Of note are also elaborate mock funerals of meat, with ‘wailing’ mourners. It may seem so, but such ‘funerals’ are not unrelated to fertility and multiplication, the coming of new life with spring, the primordial hope of regeneration through death.

A Celebration Lost and Found

The pastoral roots of these ancient festivals are palpable to this day. Clean Monday is traditionally celebrated in the country with a picnic lunch. Family and friends enjoy a colorful spread of taramosalata, pickled octopus, oven-baked beans or bean salad, spinach pie, dolmades (rice-stuffed grape leaves), together with the garden’s first crop: green onions, fresh garlic, romaine, radishes and rocket.

Pickled vegetables, among them the bitter and crunchy volvi (grape hyacinth bulbs, the lampascioni of Puglia), plus freshly cured green and black olives, are eaten with lagana, a flat dimpled bread. Lagana is supposed to be an unleavened bread, but it gradually became a focaccia-like loaf made with ordinary bread dough. Early in the morning, Athenians wait in line outside the bakeries to get a fresh crusty lagana, thus completing their picnic basket before heading towards Philopappou hill, or drive toward the outskirts of the city, to near-by villages and hills.

Kathari Deftera was, and still is, my favorite feast, not only because I love bread and all the plant-based foods. As children living in the country, my sister and I looked forward to spending time with all these kids of our age, second and third cousins, some of whom lived in apartment buildings downtown. There were few apartment buildings in those days, and my parents considered the children living in them ‘prisoners confined in cells’ who ‘ran like wild horses’ in our open garden. After my fourteenth birthday, we also moved to an apartment downtown and thus joined the majority of Athenians who drove to picturesque towns or took the ferry to the islands for the long Koulouma weekend. The excruciatingly long drive back to the city on Clean Monday afternoon in the clogged freeway made me dread these outings and the occasion that prompted them.

When I grew up I pretended to forget about my favorite open air celebration, and I often joined artists, intellectuals and journalists in the cocktail-like buffet lunch the late painter Spyros Vassiliou gave every year at his home, near the Acropolis. Vassiliou’s most famous painting is a Koulouma icon: a tin round table withlagana, olives, and taramosalata on it, along with a blue and red kite by its side.

It was after we moved to the island of Kea, in 2000, that my affection for Kathari Deftera returned.

I love to bake lagana and prepare lots of other traditional Lenten dishes. Visiting friends and relations from the city celebrate with us. I don’t even pretend to try to re-create the frugal, yet hopeful and gay atmosphere of my childhood Koulouma of the late 1950ies. My husband and I have deliberately excluded singing and dancing, and we just tolerate kites flying in the sky at a pretty safe distance. Needless to say we never ever serve barrel wine, but enjoy a selection of delicious bottled Greek wines that we taste and evaluate with our friends. We want our wine to be pure, crisp and clean-tasting, and in that sense we believe that we follow the letter of the day.

RECIPES

Smoked Herring Spread

Dolmades (Rice and Herb Stuffed Grape Leaves)

One thought on “Clean Monday: an Unusual Greek Vegetarian Feast”