The eighth stage of drunkenness according to the ancient comic poet Eubulus “is the policeman’s, the ninth belongs to vomiting, and the tenth to madness and hurling of furniture,” the very stately professor, Oswyn Murray, informed the lecture hall in his brilliant paper at the closing plenary session of this year’s Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery. During the mostly sunny weekend gathering of 230 scholars and food-lovers from England, the US, and all over the world a fair amount of wine—from Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece— was consumed, but of course participants never approached even the fourth stage of inebriation that “belongs to insults,” but there were hints of the fifth “that [belongs] to uproar.”

Long forgotten are the ancient symposia, the drinking parties of men reclined on couches sharing “the ancient Greek conception of the highest form of pleasure. They called it ‘euphrosyne’, a sense of well-being or happiness based on purely physical sensations, those of eating, drinking, music, and sex.” Citing Homer, professor Murray went on to explain that in a pre-PC (Politically Incorrect, not Personal Computer!) era, in the classical symposia “euphrosyne seems to express the general feeling, the social consequence of the pleasures of the feast.” Thus euphrosyne could, I think, describe our shared experience during this year’s 30th anniversary of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery, the theme of which, appropriately, was ‘Celebrations.’

Claudia Roden, co-chair of the Symposium with Paul Levy pointed out the humble beginnings of theSymposium. When the late Alan Davidson, the preeminent food historian and author of The Oxford Companion to Food, and Theodore Zeldin, the celebrated social historian of France, started in 1981 the interdisciplinary conference at St. Anthony’s College, Oxford, food was not considered a subject of serious studies. Today there is no respectable college or university that does not include food in the curriculums of history, anthropology, sociology, and even, we learned, biology.

Richard Wrangham, the British primatologist, professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard University, in his Friday afternoon keynote speech on ‘why we cook and why it matters,’ gave a fascinating lecture about cooked versus uncooked foods, claiming that the consumption of cooked food explains the increase in hominid brain sizes as the length of the intestines diminished and the first humans spent less time eating. He went on to argue that people have evolved to consume cooked and not raw food; the modern and very sophisticated raw eaters, who use all kinds of balanced ingredients and various appliances to mush them, never manage to get the necessary nutrients, and as a result raw-food women stop ovulating, an indication that they are malnourished, he said. Wrangham’s talk was extremely interesting, but not particularly celebratory, as some participants pointed out—probably disagreeing with his controversial, but elegant theory, which can be found in his latest book, Catching Fire: How Cooking Made us Human. Fortunately the next keynote speaker Jane Kramer, author, journalist, and for many years New Yorker correspondent, set the celebratory ball rolling describing all sorts of feasts she has taken part in, from the “trailer-trash potluck of people who celebrated their first paycheck,” to a modern pagan wedding in Martha’s vineyard, and the ‘boar dance’ in Sologne, where animal testicles are the customary delicacy.

Joelle Balhoul, professor of anthropology at Indiana University spoke about the unexpected Judeo-Muslim exchanges in North African religious celebrations, while Anthony F. Buccini – a University of Chicago researcher – examined the rules for Christian fasting and feasting. He argued that “they are to be understood in a complex way, which involves: 1) theological issues; 2) social issues, which include matters that pertain, for example, to ethno-historical identities; 3) practical or economic issues, involving, among other things, the general and seasonal availability of foods, and 4)aesthetic issues, which lie at the very heart of a given culture’s culinary life.” He said that the traditional pre-Easter Christian Lent with its stress on greens and vegetables is a Mediterranean invention that is difficult to transplant geographically to the cold northern European late winter and early spring. Enforcing Buccini’s theory about the ethnic variations of fasting,Sharon Hudgins described the Russian Lent of buttery blini, in her paper on “Maslenitsa—from pagan practice to contemporary celebration.”

Dinner parties as an art of aggression were examined by Jane Levi, treasurer of the symposium, and organizer of the Oxford Symposium on Food History, in her paper “Melancholy and Mourning: Black Banquets and Funerary Feasts.” The earliest recorded black banquet appears to be held around 89 CE by Emperor Domitian, said Levi. “In a completely black-painted room, each black couch was marked with an imitation gravestone inscribed with the guest’s name, lit by a tomb-lamp, and attended by a phantom-like black-painted boy…All the things commonly offered at the sacrifices to departed spirits were likewise set before the guests, all of them black and in dishes of a similar color. Consequently, every single one of the guests feared and trembled and was kept in constant expectation of having his throat cut at the next moment,” but nobody was killed, said Levi. Guests, “sent home in terror in the company of strange slaves…were just beginning to calm down when a messenger arrived from Domitian renewing their fears of execution. In fact the gravestones, which were silver, the dishes, which were delicious and costly, and the boys, who had been cleaned and adorned, were being sent to them as gifts.” Levi also spoke about Grimod de La Reynière, the author of the earliest food guides (the Almanach des Gourmands, 1803-1813) who hosted two of the most bizarre black banquets, the second of which held in 1813. “Friends who had only thought he’d been somewhat unwell were shocked to receive an invitation to his funeral, and all the more shockingly, at four o’clock: dinner time. When they arrived, the were met by black drapery, a torch-lit carriage with a coffin, and all the signs of a house in mourning. Then, two leaves of the door flew open to reveal a splendid table draped in black and lit by a thousand candles. Grimod himself appeared at the head of the table…”

Robert Appelbaum, food writer, lecturer at Lancaster University and at Uppsala University, Sweden, in his paper “Celebrating Solitude: M.F.K. Fisher on dining alone,” elaborated on the relevance of performance theory to the idea of a ‘celebration’ that encourages people to think of celebratory meals as ‘dramas’ of one kind or another. Although “nearly half the meals eaten in the UK are now eaten alone,” often in front of the TV, sometimes pathetically “watching programs like Come Dine with Me, where a group of four people on camera take turns providing celebratory meals for one another,” M.F.K. Fisher’s solitary dining had a different meaning, and is a recurrent theme in her early work, compiled in the collection known as The Art of Eating(originally published in 1954). “The meaning of dining alone – the significance of it, the value and the joy of it – is a crucial problem for the ethics of gastronomy that Fisher tries to construct,” said Applebaum. “A person can provide his or her own occasion, that one can momentarily celebrate one’s self, and even one’s solitude, by taking a good meal alone. Moreover, a person can play the role of one’s own audience.”

M.F.K. Fisher played a key part in Seth Rosenbaum’s paper, “W.H. Auden, M.F.K. Fisher, & Thanksgiving for a Habitat. Winner of this year’s Cherwell Prize, Rosenbaum spoke about the literary and intellectual relationship between Auden and Fisher in Auden’s late sequence of twelve poems, collected as Thanksgiving. Through archival research and close reading of the structure and text of the poems, he argued that Fisher exerted a much stronger influence on Auden’s idea of celebration than Auden scholars have previously noted. On a personal note, we are more than thrilled for this deserved distinction, as our dear friend Seth Rosenbaum is our editor on this site, and recently writes and co-edits Food Culture Index.

Robin Weir, food historian and authority on ice-cream, recreated “The torrid pleasures of an ice cream and sorbet tree in Rome, in August 1714.” During a celebration to welcome a visit from the Empress Elisabetta Cristina, “[a] beautiful vase sculpted from ice the color of alabaster, two and a half palmi(1 palmi=22.8cm/9 inches) high, was on a base in the middle of the gran Trionfo, and from it emerged a counterfeit green tree, from whose branches hung one hundred and fifty frutti gelati.” Weir partially reconstructed this improbable tree, and displayed it together with a selection of the molds and equipment used. Physicist Len Fisher, of the University of Bristol, UK, spoke about “The Great Aussie barbecue,” which is very different from its American counterpart. “Where ‘barbecuing’ means the low-temperature, slow heating of meat in a closed chamber by means of hot air from smoldering wood coals. In Australia, the meat is out in the open, and the slow heating is not infrequently replaced by blazing flames fueled by dripping fat from the sausages or lamb chops above. Instead of a slow infusion of aromas from the wood, the result can too often be a coating of charcoal,” he explained.

Celebratory Meals

More than fifty papers were presented this year, most in parallel morning and afternoon sessions during the weekend. It is impossible to follow them all, of course, but fortunately they are available at the Oxford Symposium site for the participants to read. Because papers are pre-circulated, most of the lectures go beyond the posted papers, as was the custom from the early days of the Symposium. For many years, back when the participants met at St. Anthony’s College, anyone could deliver a paper without going through a pre-selection process. Now, as participation has swelled enormously, an editorial committee—headed by Helen Saberi this year—chooses among the hundreds of proposals the ones that will be presented and included in the book with proceedings, published each year by Prospect books.

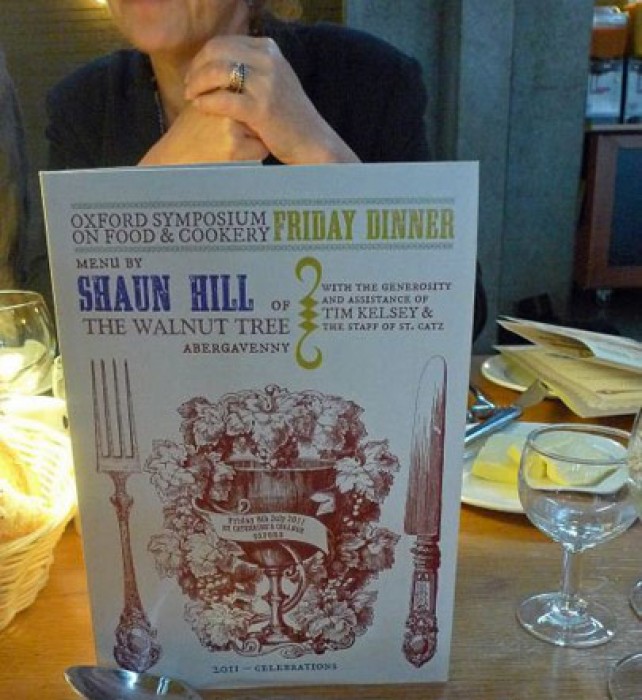

But a food conference, especially one dedicated to ‘Celebrations’ wouldn’t be complete without memorable meals. And indeed we had wonderful gastronomic experiences, starting with the dinner prepared by Shaun Hill, of The Walnut Tree restaurant in Abergavenny, Wales. The celebrated British chef, winner of two Michelin stars, describes his dishes as ‘ingredient based.’ This, of course, is what most of my favorite chefs do today, but Hill’s dishes are particularly delicious in their seeming simplicity. Drawing from his long experience and travels, he uses local ingredients with unsurpassed creativity. His seared monkfish with mustard and cucumber sauce was light and unbelievably fresh-tasting. The roast rack of lamb with summer vegetables and lamb shoulder stew that followed was equally irresistible, making us dream that we were intimately dining at a Welsh farmhouse, not in the stylish, yet crowded hall. Flawlessly serving 230 people wouldn’t be possible without the tireless Tim Kelsey, St. Catz’s chef, and his staff.

I am sorry that I had no energy left, so I skipped the tequila tasting that followed, and the opening of the “altar of remembrance to symposiasts past,” organized by Alicia Rios, the conference’s resident food artist. Saturday’s lunch celebrated the Risorgimento, 150 years of Italian unification, and it was a wonderful experience organized by Claudia Roden, Antonietta Kelly, and the Italian Trade Commission. Antipasti from various Italian regions included salami, olives, grilled vegetables, and bread brought from Sicily, plus ravioloniwith ricotta and spinach, and a wonderful chicken with rosemary and white wine. Cheeses and cold zabaglione with fresh cherries, accompanied by Malvasia Spumante Dolce from Tuscany completed this spectacular meal. Dinner was an equally spectacular, yet completely different affair: foods served during the Mexican Days of the Dead were brought to us from the other side of the Atlantic and cooked by Fernando de la Cruz, and the brothers Sage Bernard and Tom Conran. Tamales, mole Poblano, and delicious anise-flavored breads, ominously shaped as skull and crossbones, were accompanied by Mexican beer and Spanish wines.

These were very difficult acts to follow, the standard had been set high, and I hope that the Sunday lunch I prepared, the last meal of the symposium, did not disappoint. The theme, and my symposium paper, wasKathari Deftera (Clean Monday), the unique vegetarian Greek feast that marks the first day of Lent. Devoid of any official help—as you may have heard, Greece is amidst momentous crisis, I enlisted my generous friends who helped turn an idea into a meal for 230. We served the traditional meze spread: black dry-cured olives from Thassos, large green olives from Rovies, Evia, taramosalata, grilled Florina peppers, baked giant beans, and marinated octopus imported and donated by Odysea. Akakies, a fruity rosé, and Petra, a crisp white wine offered by Kir-Yanni, accompanied the dishes. For dessert, I complemented the customary sesame halva with lemon marmalade that I prepared using the last fruits of our trees from my garden on Kea. I was terribly anxious to see if the meal would come together, but thanks to the invaluable help of Tim Kelsey, who made a wonderful potato salad to complement the octopus, and served everything so tastefully, people seemed to have really enjoyed our lunch.

Contrary to most food conferences, the Oxford gathering is not commercial and relies on participation fees and individual donations to cover the substantial cost. Since the conference has grown significantly, it is held in the magnificent St. Catz college, a landmark, Oxford’s only Modernist college, designed by Arne Jacobsen. The American friends of the symposium – headed by Ray Sokolof, (president), Barbara K. Wheaton (vice president), Doug Duda (secretary), and Cathy Kaufman (treasurer) – are particularly active in publicizing and collecting donations from the other side of the Atlantic. Next year’s Symposium will explore “Stuffed & Wrapped Foods,” and as it will be held a few weeks before the London Olympics (July 6—8, 2012) it is expected to sell out fast…

Hola! I’ve been reading your web site for a while now and finally got the bravery

to go ahead and give you a shout out from Houston Texas!

Just wanted to say keep up the good job!